"The aim of Positive Psychology is to catalyze a change in psychology from a preoccupation only with repairing the worst things in life to also building the best qualities in life."

Martin Seligman

Positive Psychology

Emergence: Positive psychology is a branch of psychology focused on the scientific study of well-being and human flourishing, emerging as an organised field in the late 20th century. It arose in reaction to the traditionally dominant “disease model” of psychology, which emphasised mental illness and maladaptive behaviour to the neglect of positive aspects of life. Throughout much of the 20th century – especially after the World Wars – psychological research and practice concentrated on treating psychopathology, often overlooking the qualities that make life most worth living. In contrast, mid-century humanistic psychologists such as Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers advocated a more growth-oriented perspective, encouraging the study of healthy human development, happiness, and purpose. Maslow even coined the term “positive psychology” in 1954, critiquing the field’s preoccupation with dysfunction and calling for greater attention to human potential and thriving. These early ideas laid the groundwork for a new movement that would formally take shape decades later.

Early Work: The modern positive psychology movement was spearheaded by Martin E. P. Seligman, who in 1998 used his platform as President of the American Psychological Association to champion “positive psychology” as a theme for the discipline. Seligman’s initiative, co-developed with others like Mihály Csíkszentmihályi, aimed to redirect some of psychology’s focus from repairing the worst in life to building the best in life – in essence, to establish a science of human flourishing. In a seminal article introducing the field, Seligman and Csíkszentmihályi outlined a framework for studying positive mental states and qualities. They envisioned a “science of positive subjective experience, positive individual traits, and positive institutions” that would improve quality of life and help prevent the pathologies that arise when life is meaningless. At the same time, they cautioned that psychology’s “exclusive focus on pathology…results in a model of the human being lacking the positive features that make life worth living”. Early research in this vein explored topics like happiness, hope, creativity, and optimism, signaling a clear divergence from the illness-centric approaches of the past. The foundational figures of the field – Seligman above all, alongside colleagues such as Csíkszentmihályi and Christopher Peterson – helped to legitimise this shift in focus, publishing influential works and establishing positive psychology as a credible scientific domain. By the early 2000s, the movement had coalesced into a robust research agenda, supported by new journals, conferences, and graduate programmes devoted to the empirical study of positive human functioning.

Key Concepts: Central to positive psychology is the concept of well-being – a broad construct encompassing subjective satisfaction, positive emotion, meaningful engagement, and optimal functioning. The overarching aim of the field has been to understand and foster the conditions under which people thrive, rather than solely fixing what is wrong. This strengths-based approach stands in contrast to deficit-focused models: positive psychologists emphasise identifying and building on individuals’ strengths and virtues as a pathway to well-being . For example, Peterson and Seligman’s Character Strengths and Virtues handbook (2004) provided a classification of 24 character strengths under six core virtues, a deliberate counterpoint to the diagnostic catalogs of mental illness. Over time, the aims of positive psychology have evolved and expanded. Initially, the field was often associated simply with the study of happiness and life satisfaction; however, its leaders soon elaborated a more nuanced view of human flourishing. Seligman proposed a formal well-being theory and in 2011 introduced the PERMA model, which identifies five key pillars of flourishing – Positive emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment. This model reflected an evolution from an earlier focus on happiness alone to a multifaceted understanding of well-being as the outcome of various interrelated factors. Today, positive psychology continues to refine its concepts and applications, but its core mission remains the study and promotion of the positive qualities of life. It has shifted the lens of psychological science toward exploring how individuals and communities can thrive, building on strengths to cultivate a life of fulfillment and resilience – a true science of human flourishing.

Application: Positive psychology – the scientific study of strengths, well-being, and optimal functioning – has rapidly grown into a major influence on personal and organisational development. Core concepts such as strengths-based development, well-being frameworks, and Seligman’s PERMA model are increasingly operationalised in self-help, coaching, and business consulting. These evidence-based approaches aim not only to improve individual happiness and health, but also to boost performance and quality of life in organisations. A wave of positive psychology interventions (PPIs) – practical exercises like gratitude journaling, strengths identification, mindfulness, and optimism training – has entered mainstream self-help literature. Such interventions, often delivered via books, apps, or workshops, have shown small to moderate improvements in well-being and stress reduction for general populations. For example, practicing gratitude or using one’s character strengths correlates with boosts in positive emotion and resilience, outcomes documented in multiple studies and reviews. While not a panacea, these “self-help” style PPIs represent a translation of science into everyday personal development tools.

Coaching has likewise embraced positive psychology principles. Positive psychology coaching (PPC) applies a strengths-based, goal-focused lens to the coaching process. Rather than treating pathology, coaches help functional individuals identify and build on their strengths and values to flourish, aligning with positive psychology’s focus on “what helps ‘normal’ people thrive”. Research indicates that blending coaching with PPIs can amplify benefits – the personalised guidance of a coach can improve “person-activity fit” and sustain positive outcomes better than one-size-fits-all exercises alone. For instance, clients who receive strengths feedback and coaching show greater gains in goal attainment and life satisfaction than those using self-help exercises without coaching. Overall, U.S. coaching and self-development programmes increasingly draw on positive psychology’s evidence base – from the use of VIA character strengths surveys in life coaching, to “happiness” courses and apps grounded in well-being science – reflecting a shift toward strengths, meaning, and resilience in the personal development culture.

Positive psychology’s impact is equally notable in organisational development. The corporate world has seen a surge of strengths-based development initiatives and well-being programmes inspired by positive psychology findings. In contrast to deficit-focused models, many companies now strive to create strengths-based cultures that “give employees a chance to do what they do best every day” instead of fixating on weaknesses. Emphasising employees’ core talents has been linked to higher engagement and lower turnover – Gallup reports that workers who use their strengths are six times more engaged at work. Aligned with this, leadership coaching and HR practices increasingly use tools like the CliftonStrengths assessment to identify and cultivate individual strengths, aiming to improve both well-being and productivity. This strengths-centric approach marks a practical adoption of positive psychology in management consulting and training, often yielding improvements in team performance, creativity, and job satisfaction.

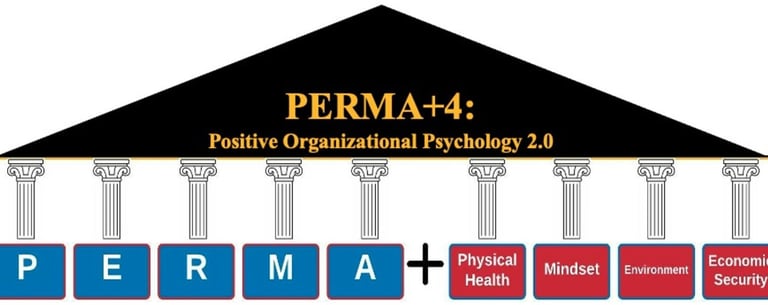

The PERMA+4 framework expands Seligman’s original PERMA model by adding four additional pillars – Physical Health, Mindset, Work Environment, and Economic Security – to better encompass workplace well-being (illustrated as four extra “columns” supporting the PERMA roof). This holistic model exemplifies how positive psychology well-being frameworks are adapted in real-world organizational settings, providing a comprehensive blueprint for employee development and wellness programmes. By integrating factors like physical wellness and financial security, PERMA+4 reflects the recent trend toward more holistic employee well-being strategies in business consulting.

Beyond PERMA, other research-based constructs from positive psychology have entered organisational practice. For example, Psychological Capital (PsyCap) – a combination of hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism – is taught by consultants as a developable asset for employees, shown to correlate with performance improvements. Likewise, methodologies such as Appreciative Inquiry (focusing on a company’s successes to drive change) and positive leadership training programs draw explicitly on the science of optimism, positive emotion, and meaning at work. These applications, often termed Positive Organisational Scholarship or Positive Organisational Psychology, aim to enhance both the “effectiveness and quality of life in organisations”. Notably, meta-analyses indicate that such positive organisational interventions can improve outcomes like work engagement, team cohesion, and innovation. Although the empirical effect sizes are sometimes modest and context-dependent, the infusion of positive psychology into workplaces represents a paradigm shift – viewing employee well-being and strengths as key drivers of sustainable success, not just as afterthoughts.

Positive Culture Ltd: At Positive Culture, we emphasise the use of these evidence-based techniques for fostering individual and organisational well-being and resilience - applying the science of well-being to flourish together. By implementing positive psychology principles we support organisations to implement well-being frameworks (including PERMA) to design employee development and mental health programmes, as we translate cutting-edge research findings into tangible strategies for improving workplace well-being and engagement. This positive psychology approach helps companies move beyond mere stress reduction to cultivating a fulfilling, strengths-driven work culture that boosts both morale and performance. Our leadership development programmes and HR initiatives include strengths assessments, resilience training, and coaching for meaning and purpose at work.

The science of positive psychology has become a force in personal and organisational development – providing frameworks for well-being and strengths-based practices that can be operationalised towards leveraging human potential and well-being as central to development in the 21st century.

Bibliography:

Csikszentmihalyi, M. and Seligman, M.E.P., 2000. Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), pp.5–14.

Donaldson, S.I., Dollwet, M. and Rao, M.A., 2015. Happiness, excellence, and optimal human functioning revisited: Examining the peer-reviewed literature linked to positive psychology. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(3), pp.185–195.

Gallup, 2020. State of the American Workplace Report. Washington, DC: Gallup Inc.

Govindji, R. and Linley, P.A., 2007. Strengths use, self-concordance and well-being: Implications for strengths coaching and coaching psychologists. International Coaching Psychology Review, 2(2), pp.143–153.

Kauffman, C. and Linley, P.A., 2007. A practitioner’s guide to positive psychological coaching. International Coaching Psychology Review, 2(2), pp.168–178.

Luthans, F., Youssef, C.M. and Avolio, B.J., 2007. Psychological Capital: Developing the Human Competitive Edge. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K.M. and Schkade, D., 2005. Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology, 9(2), pp.111–131.

Niemiec, R.M., 2018. Character strengths interventions: A field guide for practitioners. Göttingen: Hogrefe Publishing.

Oades, L.G., Steger, M.F., Delle Fave, A. and Passmore, J., eds., 2017. The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of the Psychology of Positivity and Strengths-Based Approaches at Work. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

Peterson, C. and Seligman, M.E.P., 2004. Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Seligman, M.E.P., 1998. President’s address. American Psychological Association Annual Convention, San Francisco, CA.

Seligman, M.E.P., 2011. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being. New York: Free Press.

Snyder, C.R. and Lopez, S.J., eds., 2002. Handbook of Positive Psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Van Zyl, L.E. and Stander, M.W., 2019. Positive psychological coaching: A meta-theoretical framework for the development of a coaching psychology practice. International Coaching Psychology Review, 14(1), pp.70–85.

Waters, L. and Sun, J., 2016. Can a brief strength-based parenting intervention boost self-efficacy and positive emotions in parents? International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 1(1), pp.41–56.

Wong, P.T.P., 2011. Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Canadian Psychology, 52(2), pp.69–81.

Positive Culture

Empowering people and organisations through the application of positive psychology.

CONTACT

SUBSCRIBE

0845 527 1009

© Positive Culture Ltd, 2025. All rights reserved.

Positive Culture Ltd is registered in England & Wales (company reg: 14606776)

Links